Strangers Drowning

Ms MacFarquhar profiles several people who have chosen the "do-gooder" life, and interposes some reflective interludes in between the biographies, questioning whether what she terms as "morality" ought to be "the highest human court" and whether such morality might even compromise what it means to be human.

The conclusion of highest morality, as Ms MacFarquhar has defined it, seems at odds with what would seem right to most of us. Preferring to save a family member feels right. Sheer utilitarianism feels monstrous. It ought to mean something when it's a loved one, as opposed to a stranger.

One person concluded that, if the same amount of money could pay for her mother's medical treatment, but could also save a hundred children's lives in a Third World country, then she would choose the children.

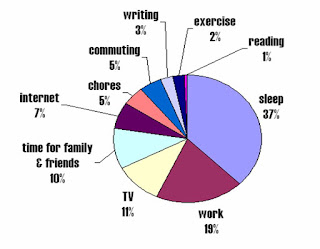

Another person chose to live on what he termed the World Equity Budget (total global income divided by total global population - which unfortunately is a very small sum) and to give away everything else. When his wife of 30 years and children objected, he had to choose between his family or his commitment to the World Equity Budget. He chose the budget and left his family.

Despite the objective admiration I felt for their commitment to a moral ideal, I was turned off by coldness and purity of the whole matter.

In line with the theme of Ms MacFarquhar's book, the essay explores the Badeau family's thinking about why they kept on adopting additional strangers as children, despite knowing the terrible sacrifices of time, energy and resource left available to themselves and their own children, including those they had already adopted.

Every time they adopted a child, they felt new love for him. Sometimes they felt the beginnings of love even before they met the child, even before they saw his photograph. It was like the feeling you had when you learned you were pregnant. Sue said: you didn't know the child, the child barely existed; and yet you loved him.

But they didn't. All their adopted children came from very difficult backgrounds or with serious illnesses. Despite the Badeaus' work and prayer, there were multiple teen pregnancies. Deaths. Quarrels within the family. Run-ins with the law. The Badeaus struggled and doubted themselves many times.

Yet Ms MacFarquhar's essay on the Badeaus concludes quietly and triumphantly.

And every year there were birthday parties and weddings and graduations; there were grandchildren and great-grandchildren, most of them still living in the same neighbourhood, within a few blocks of each other and their parents, in and out of each other's homes all the time, minding each other's children.

And every Easter and Fourth of July and Thanksgiving and Christmas and New Year's, the children and grandchildren and the great-grandchildren gathered with Sue and Hector in the big house they still lived in, although they couldn't afford it, and ate a meal together. And though some were missing - three dead, one in jail - still, most were there year after year, and for everything that had happened, they were a family.

This is very much the story of God's love for us, even while we were strangers to Him.

"God demonstrates his own love for us in this: While we were still sinners, Christ died for us." Romans 5:8

Yet He did so, not in adherence to some cold moral code. No. He did so knowing that we were to be His children and family. John 3 explains that a Christian is born again, of the Holy Spirit.

"The Spirit you received does not make you slaves [to sin, or even to a moral code!]... rather, the Spirit you received brought about your adoption to sonship... The Spirit himself testifies with our spirit that we are God's children." Romans 8:15-16

Altruism at scale is admirable, fair and just. But there is something even beyond fairness and justice. There. Is. Love.

Note: if you would like to read Ms Farquahar's full essay, you can borrow the book Strangers Drowning (it's the chapter called "The Children of Strangers") from the National Library, or you can go to the original 2015 New Yorker article (you get one free article!). The link is here. It's quite long, but very well worth the read.

Comments